Three Montana Properties Nominated for National Register Listing

Two 'cabins' and a beacon may be added to the list

Three properties recently were nominated for listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

Two of the properties are log cabins – one in Flathead County and the other in Jefferson County – that highlight the diversity of homes built of local materials in different areas of Montana, as well as the different reasons for the construction of the two homes. The third nomination is for the 55-foot-tall St. Regis Airway Beacon in Mineral County, which was used to guide air traffic off and on from 1935 until 2017.

“These nominations show the variety of property types eligible for the National Register,” said Pete Brown, program manager for the State Historic Preservation Office. “Certainly, an airway beacon is not something most people think of as a historic site, but it’s a utility that facilitated express transport in the era of trains, well before interstate highways.”

The log homes are an interesting contrast to each other. The occupant-built Kruse Cabin is hardscrabble rustic; scratched out of nature as a place to escape the North Fork’s harsh elements in life’s hustle. But the Hall Bungalow is stylized rustic; designed and built by specialists as an urbanite’s retreat. It had comforts like electric lighting and upholstered furniture. It’s easy to picture its well-healed, seasonal occupants meeting nature on their own terms from the house’s front porch.

Like all National Register properties, these properties tell a nuanced part of Montana’s story that might not otherwise be told.

Every review board meeting consists of nominations that allow a better understanding of Montana history,” said John Boughton, National Register coordinator. “The three nominations heard at the latest meeting in September continue the trend of properties that have their own special history, unique to them.”

The Hall Bungalow

Started in 1916 and completed in 1917, the Hall Bungalow reflects its history as a private summer residence initially, and later as a ranch house for an operating cattle business. Two of the earliest property owners, James Hall and John Scoville, lived in Chicago, while the third principle, Harold “Sol” Hepner was a Helena attorney who served in the state legislature and as Lewis and Clark County attorney. William Martin, a Chicagoan, was with the Chicago Board of Trade as were Scoville and Hall. Together, the four men were part of the Hall Ranch Company.

Although the house was elegant, it primarily served as a summer home. When the Hall Ranch Company sold the property to John “Jack” Lowrie Patten for $150,000 in 1919, it was estimated to be the largest real estate deal ever in the county. He renamed the ranch the “Lazy T Ranch” and hired as many as 22 men for haying and grain harvesting.

Patten moved to Chicago in 1922, after he and Courtney Gleason, a Chicago real estate broker, traded the ranch for a deluxe apartment building. Like many brokers, Gleason didn't’t want to run the ranch but considered the property as a long-term holding. That appeared to backfire, after he sold the property at a substantial loss to the Lazy T Ranch Corporation of Whitehall in 1932.

Finally, in June 1928, Paul and Vivian Smith bought the ranch and moved there full-time in 1953. It remains in the Smith family, with Paul and Vivian’s children placing it in a conservation easement in 2020 to preserve its agricultural heritage for future generations.

The home strongly retains its historic appearance and character in its rural setting in the Boulder Valley, notes Joan Brownell in her nominating petition. It’s an unpretentious but elegant log residence about 10 miles southeast of Boulder.

The building is symmetrical and U-shaped, with the log interior walls pulling people seamlessly from the exterior into the interior. Brownell notes the excellent craftsmanship of the Hall Bungalow is readily apparent.

“Walking into the Hall Bungalow, one is immediately struck by its grandeur and almost formal gravitas,” Brownell wrote. “The interior is not ornate but presents a stately yet comfortable appearance as it displays fine craftsmanship throughout. … The tongue-and-groove ceiling and wood floors throughout the house further distinguish the interior.”

Upon entering, the massive river-rock fireplace dominates the interior north wall. To the left of the fireplace are French doors that once opened into the screened-in porch but are now inaccessible by a square piano brought to the Boulder Valley in the early 1880s.

To the right of the fireplace stand original built-in cabinets on either side of a framed opening without doors. The living room holds a wrought iron chandelier with mottled glass and other historic light fixtures of the same design.

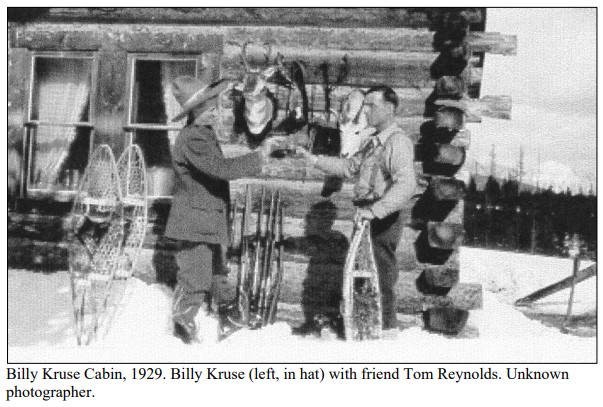

The Billy Kruse Cabin

Also erected in the early 1900s, the Billy Kruse Cabin is historic due to the owner’s untimely demise over a “legendary” woman.

Wilhelm Axel Christian Kruse, a Danish emigrant, built the cabin in the North Fork of the Flathead in 1925. Kruse was described as “possessing a medium height, stout build, brown hair and blue eyes,” according to National Register documents compiled by Lois Walker. But he allegedly also possessed a bad temper, especially when drinking.

The single-pen cabin was constructed from locally available timber and boasts a small log addition that displays, as does the original cabin, well-crafted square notching on its corners. The cabin’s entry occurs on an eave wall, an uncommon location for many of the cabins in the North Fork area. The tight construction is evidence of the builders’ skills.

The original 16-by-18-foot cabin is built of hand-peeled larch logs stacked 13 high on the gable ends. Each log tends progressively smaller, except for one. It has 8-foot ceilings on the main floor, with a sturdy staircase leading to the second floor.

“The cabin stands as a testament to those who envisioned a place of their own in the rugged mountains of northwest Montana,” Walker notes in the nominating paperwork. “Many hoped that the land would sustain their way of life in this remote area but found it necessary to seek additional outside income.”

Loneliness was a constant companion for many of the Flathead bachelors. According to Tom Reynolds, a friend of Billy Kruse, in 1931 he became acquainted with a middle-aged woman from New York City through what Reynolds called, “a Hearts and Hands piece in some newspaper.” Though separated, Mary Powell was married with three children.

“Perhaps for financial reasons, or possibly because she was enamored with the idea of relocating to the remote Rocky Mountain West, she agreed to come live with Billy as a housekeeper/companion, bringing one of her daughters with her,” Walker wrote. “The end result of this relationship turned out to be very unfortunate.”

Kruse often left for extended periods to work for the Forest Service and as a sheepherder. During one of the trips, the Powell women moved into one of two homes of Kruse’s neighbor and friend, Gustav “Ed” Peterson. That enraged Kruse upon his return, according to a book by John Fraley.

After a night of drinking and threats, Kruse shot at Peterson and missed. Peterson returned fire and fatally wounded Kruse.

Afterward, Powell became a legendary figure in the North Fork, Walker wrote. She was known as “Madame Queen” and allegedly became a bootlegger, stayed with a variety of men, and eventually left the North Fork area.

The privately-owned cabin changed hands numerous times and is now a popular stop on history tours of the North Fork. It’s commonly called the Madame Queen Cabin.

St. Regis Airway Beacon

The beacon tower sits at an elevation of 4,277 feet on a mountain within the Bitterroots, overlooking the Clark Fork River and I-90. It was erected on state land in 1935.

The steel tower measures 9-by-9 feet at the base, with each corner resting on concrete footings. The tower tapers to 4-by-4 feet at the top and supports a 6-by-6-foot steel grate platform on which a revolving beacon sits. A vertical lightning rod projects from the northwest corner of the platform.

The Montana Aeronautics Division upgraded the beacon with a pulse start lamp kit in 2011.

“The isolation of the property high in the mountains provides for a strong sense of integrity of location, feeling, setting, and association,” wrote Jon Axline, a historian with the Montana Department of Transportation, who prepared the nomination form. “The original beacon pedestal and light dome still sit atop the platform, and the course lights remain. MDT continues to actively maintain the tower and associated warming shed and electronics building.”

He notes that a nearby warming shed still contains the distinctive table that also functioned as a shutter, and the bed pallet. The warming shed was built sometime after World War II as a haven for beacon maintenance crews in adverse weather.

The beacon played a significant role in aviation history, particularly the safe nighttime navigation of commercial and private aircraft across western Montana and the towering Bitterroot Mountains beginning in 1935.

It was turned off and on, but left in place, until it was permanently retired from navigational purposes in 2017. However, it still is used for radio repeater equipment and is routinely maintained.

“The St. Regis Airway Beacon and its associated resources illustrate the federal development of the country’s airway transportation corridors with its nascent beginnings in 1926,” Axline wrote. “Between 1926 and 1938, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Air Commerce created 18,000 miles of airway corridors in the United States and installed 1,550 airway beacons to mark the corridors for night flying. The establishment of the airway corridors signaled a profound event in the evolution of the nation’s air transportation system.

“The beacon is a relic of past Montana aviation history that represents an important phase in the evolution of aviation in the United States. For almost 80 years it provided a navigable airline corridor and reassurance to hundreds of pilots who continue to fly over the Bitterroot Mountains.”